BEING BRITISH - AND WHAT IT MEANS

As part of the British Values Survey, we ask people to select any number of items, from a list of 31,

that they consider "important to their identity - who they feel they are". One of those items is "Being

British" and here we take an in-depth look at those people who 'self-identify as British' (abbreviated

as SIBs).

Values: Settler (index 115) and Prospectors (index 112) are both significantly over-indexed, but Pioneers are significantly under-indexed (index 78).

Demographics: There is no significant variations by gender or socio-economic group. All under 45s are under-indexed, but not significantly except in the 22-24 category (index 70); and the over-indexed are more represented in the over 65s (index 134)

Selecting as many items as they desired from a list of 31 descriptors, only 34% of the British population chose “Being British”.

This figure may surprise many people who have assumed that 'everyone' thinks they are British, since all survey respondents live in the UK.

But, taking a step back, it should be obvious that not everyone who lives within the boundaries of the islands, or those who once lived here, identify with this ethno-geographical description when thinking about their own identity.

Self-identity - the way people think of themselves - is usually a stronger base from which to understand both oneself and others than via something that is assigned to you by way of birth (gender, genetics, etc.) or happenstance (where you live, what you have accomplished to date, etc). People can accept the vagaries of birth or happenstance but 'choose' to self-identify differently. By quantifying how many people within a population choose different options, decision makers can begin to identify:

a) the purpose behind the chosen option and

b) the number of people within the culture who express it.

This is important when setting policy decisions that affect organizations; or developing strategies that support different social agendas; or building commercial brands that will appeal to specific target market values and beliefs.

Experience shows that policies, positions and brands that create platforms and appeals, predicated on the idea that people living in Britain will somehow magically identify with communications and events that express 'Britishness', often fall far short of expectations.

Here we offer a part of the explanation for this, and also a chance to deploy appeals more efficiently to Britishness.

To be fair to decision makers, they have still used one of the most frequently chosen factors of self-identity in the UK.

Although only 34% of the population claimed this factor as being an important part of their identity – it is the third most frequently chosen factor from the list of 30.

Cultural narratives – created to serve vested interests and mass media platforms – often drive perceptions, which ordinary citizens use to frame their thoughts and behaviours.

Being able to understand clearly the extent of media speculations and proclamations about 'the British' and 'pride in the ceremony and history of the British traditions' is useful to both the man in the street and decision makers.

Knowing the limits to which a statement, policy or brand can be pushed is vital, when attempting to change or reinforce individual thoughts or social behaviours.

To move beyond broad generalizations about 'the British' it is more useful to look into the world of the people most receptive to policies, procedures, positioning’s and communications that match their own self identity as 'being British'. This will build a more granular picture of how they are different from the other 66% of the population.

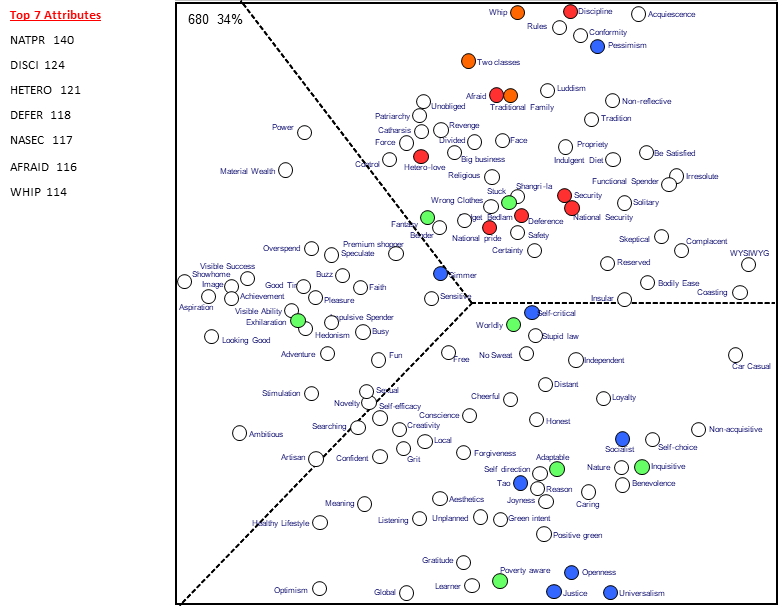

The Attribute Map on the first page lists the seven most espoused Attributes among the 34% who feel and think being British is an important part of their identity – and it helps us understand them in their own terms and how they differ from others.

The most defining of the 118 Attributes for this group of people is their sense of NATIONAL PRIDE:

It is important to me to take pride in British history and traditions. I am proud to be British.

Those self-identifying as being British (let’s call them "SIBs") are 40% more likely than the rest of the population to be proud of their history and tradition. This doesn’t mean that others not choosing being British (non-SIBs) are not proud of their history and tradition, it merely means they are not defined by it.

At the time of writing this, the Queen is lying in state in the Great Hall of Westminster and miles-long queues of people of all identities are waiting to walk past the coffin. Many will be there as a sign of respect for the lifetime she performed her duties and fulfilled the obligations of her assigned position in the country. Many among the queue will be there because of their national pride; but it’s also likely that many others will be present for reasons other than being British, let alone because they espouse national pride.

Whereas national pride might seem obvious in having a high index in relation to being British the second highest could seem to some to be more about being 'right and proper'. To many, this may seem outdated and not at all right and proper in the modern world.

The Attribute DISCIPLINE is almost a quarter (24%) more likely to be espoused by SIBs:

I believe that strict discipline is in a child's best interests. I think that criminals should face severe sentences to deter them from offending again.

Looking at the Attribute Map, it can quickly be seen the Discipline is on the very edge of the values space indicating that this is not a central Attribute among the general population.

However, it is the second most over-indexed among SIBs. Other research shows that this is an orientation that is gradually fading out – with the oldest segments of the population agreeing with it more so than younger age groups.

It can be conjectured that the cultural wars so beloved of the media, when British history, or traditional teaching is questioned, is often fuelled by this type of concern. It creates the cultural battle lines and provokes disruptive social commentaries around the issue of what it means to be British.

This Attribute can be seen as a basic virtue among SIBs. In this psychological orientation they are likely to react to challenges to their point of view. Setting boundaries to children’s behaviour is important to them and some of today’s more liberal attitudes in this respect make them angry at other parents. Similarly, they are more likely to be proponents of longer custodial sentences and more punitive community services for criminal acts.

Emotionally, SIBs feel that rejecting DISCIPLINE is not a sensible way of being. A failure to be sensible is likely to lead to ‘everything falling apart’. This can lead them to believe that more socially liberal attitudes and practices are ‘the root of the problems we have today’ - and something to be eradicated as soon as possible. This emotional response is socially powerful and creates one of the battle lines in the cultural and values wars at this point in history.

It is important to keep in mind one of the many researchers’ mantras – this is how a subject feels and thinks – it is neither right nor wrong – it is purely an empirical measurement.

The next aspect of the SIBs is the Attribute HETERO LOVE:

I believe that a man is not complete without a woman to love - and that a woman is not complete without a man to love.

During the reign of Elizabeth II this has gone from "obviously correct" to "it is a matter of individual choice who to love and it isn’t really about gender".

In the early 1950s, amongst the general population, the espousal of HETERO LOVE would have been supported by a legislative agenda that placed boundaries around what kinds of love were socially permissible and which were not. Strangely, while male homosexuality was a serious criminal offence, the very idea of female homosexuality was not considered as a suitable topic for consideration, by (dominantly male) lawmakers. The acceptance of this Attribute drove many ideals of behaviour in the young Queen’s country. Relationships and families were created within this romantic ideal.

Many intellectuals have engaged in understanding, defining and celebrating this aspect of life – its acceptance, rejection and the individual and cultural consequences of them. Many definitions of traditional romantic love – for that is what the Attribute is measuring – have been elucidated over time and it was still conventionally socially accepted in the UK 70 years ago.

Today, social movements, some driven by legislative changes and evolving social values, have given a different meaning to it. At the end of Elizabeth’s reign, it has become somewhat contentious, though still accepted by broad swathes of the community, despite new social perceptions of gender and family.

But it is fair to say that SIBs would still hold onto the romantic vision of ‘completeness’ as love between a man and a woman. To them it is a given, and a basis for their social and intimate lives – a marker that should be unquestioned and that produces strong emotions when it is challenged. It produces equally strong emotions when it is affirmed through the observance of it. An examples would be the wedding of a man and a woman - but not of people of the same gender. Another example might be the formal celebration of a continued loving relationship – within families for sure, but also for cultural icons up to and including the late Queen and her husband.

The death of the Queen was as symbolic as it was actual. Her symbolism was as a source not just of stability, but of a loving stability. The challenge to the Royal family, of remaining salient within the minds of people who value their Britishness, will be the way in which the new King and Consort fill this role – in their own way – as a way to bring stability in the harsh times that are likely to define the opening years of the King’s reign.

It is likely that he will be judged differently – because of the Diana part of his life – than will be the case of his heir.

The new Prince of Wales, William, and his wife have been presented as the social icons of a loving family and will be part of the social narrative that defines Britishness for years to come. Despite the negative press in the UK about Prince Harry and his wife, he is still a romantic figure in the minds of the self-proclaimed British. His love for, and desire to protect his family is paradoxically British - at the same time as he trims back his born-into Royal obligations, he is taking on the task of duty and loving care of his family. Both of these relationships, and their young families, are models of the romantic ideal prized by SIBs.

Following on from this, perhaps surprising, insight into the psyche of those who feel being British is an important part of their identity is the next most espoused Attribute – which is over-indexed at 118 (18% more likely than the rest of the population) – and measures what is defined by CDSM as DEFERENCE:

I believe it is important to show respect to people in authority. I think people should be patient.

This would seem to typify a cultural stereotype of ‘the British’ having a sense of ‘knowing their place’ and being faintly subservient – biding their time – while letting the world ‘get on with it’. To some extent, this is correct – more so among the Settlers, who are even more over-indexed in this orientation.

These Settlers, who over-index the most (114) and espouse DEFFERENCE, are deferent because they desire structure in their lives. Knowing the rules, and obeying them, is important to them. Stability more than change is something they prize - and any redefinition, or even questioning, of their Britishness is something that causes anxiety, if not outright hostility.

Respecting authorities is a statement that reflects their values that ‘safety in a changing world’ - in liminal moments, like the week the Queen died – is more important than questioning the role of monarchy, the ultimate authority.

Instead of crowds of people congregating to get one last ‘glimpse of the Queen’, many of these people formed the miles-long queues to respectfully pay last homage to a person most of them had never met, but of whom most had memories precious to them. The queues were a reflection of their respecting of authorities and of patience.

It is likely that many of them would not have given much thought about the Queen before her death, but feel an affirmation in their own identity through the public celebration of her life

In the Britain of 2022, they are not ‘old fogeys’ – though the majority of the Deference espousing Settlers are over 55 years old. These Settlers fully support taking care of others like themselves, often not waiting for authorities to act. They appreciate that high level decision makers are unlikely to move as quickly as people like themselves, who they feel they can fill in the gaps before official assistance is available in times of need. There is a time for action, and there is time to restrain criticism and exercise some patience. "Keep Calm and Carry On" could be their motto.

But it isn’t just the Settlers who espouse DEFERENCE. Over 70% of SIBs that espouse DEFERENCE are either Pioneers or Prospectors. It is clear from the data that each is motivated by their particular values-set, while also self-identifying as British.

For example, the DEFERENCE espousing Prospector SIBs are 79% more likely than the general population to be houseproud and expend time and effort to decorate it the best they can; to be in the right area; with the right schools, jobs, amenities – proud to be British and knowing it is about maintaining stability so that they have the time to ‘improve’ whatever it is they value.

This looks and feels more like a Middle England version of Britishness. Demographically, this peaks among the 25-44 age group. They have come out of Covid lockdowns and furloughs and are facing an uncertain and deteriorating economic future. They are not looking for a revolution; they will defer to authorities - if those leaders can ensure ‘delaying gratification’ will pay-off in the end.

The DEFERENCE espousing Pioneer SIBs, on the other hand, are 69% percent more likely to espouse the Attribute GRATITUDE - the feeling that they have much to be grateful for. With this orientation comes as sense of time that has led them to this point in their life; and life goes on, time goes on, and having the patience to wait for the good things is a virtue. ‘Authorities’ come and go, but life goes on – criticising authorities can often seem no more than self-indulgence.

But what is really important to understand is an Attribute that links these two very different Groups – Prospector and Pioneer SIBs – and presents a more positive light on deference amongst them. This is JOYNESS - the sense of joy they feel in others’ successes. This is at times manifest in their joy for their children’s successes, or their parents’, or individuals and groups in their local communities who have worked long and hard for something they believe in.

This joy is also often manifested in major events or mass gatherings where skills, developed over years and decades, can be exhibited and lauded by multitudes of others. Large sporting events, like the Olympics and World Cups, where years of delayed gratification (grinding out days and nights under the tutelage of those in authority – coaches, managers, trainers - learning a craft without recognition) climaxes at major events. The Pioneers and Prospectors recognize others’ successes as an affirmation of their own deference to authority as they build for a better tomorrow and live a life of gratitude.

Truly, the joy of patience and deference is an integral part of their Britishness.

The next most espoused Attribute by the SIBs is a natural extension of NATIONAL PRIDE. This Attribute it is less counter-intuitive than HETERO LOVE and quite easy to relate to - the espousal of NATIONAL SECURITY:

It is important to me that my country be safe from threats from within and without. I am concerned that social order be protected.

Once again, preserving order runs through the British values set. The common thread that links Britishness is the stability that it provides in an ever-changing world. This profile is being written as the Queen lies in state and hundreds of thousands of people, many of them SIBs, have walked and waited patiently for hour after hour to exist in the same space as the manifestation of the stability of the social order and ultimate well-spring of protection of their country.

Many words have already been written and spoken, and many more in the decades and centuries to come will talk of this moment – analysing, interpreting, decorously debating and angrily arguing what this moment ‘was’ and what it ‘meant’.

“What the British thought, felt and did” in this moment of fear (for the world and themselves) uncertainty (about how to cope if worse comes to worst) and doubt (that there is an answer to any of the problems affecting them) will fill missives and tomes.

Yet many will not really get to the roots of why the snaking lines of people, full of strangers, at times in the cold of night, would all connect and share the stories of their lives, and what it meant to them on an individual basis. An openness in the world city unlike anything since the horrific Blitzes of the Queen’s childhood.

During the wartime Blitzes – which virtually no one in the lines experienced - the differences between people broke down into a common identity of "British" as their physical security was threatened. Thankfully no bombs created the conditions for this new coming together.

The 70-year monarch was being laid to rest - and with her a sense of an immutable present. Times change but the young Queen/the motherly Queen/the grandmotherly Queen was always there in the lives of almost all the people – and more so in those to whom being British is an important part of their identity.

The safety, security and sense of belonging that is important to these people was thrown into the forefront of their minds, raising questions they hadn’t needed to ask previously – important questions about self-perception, how to react to FUD factors (fear, uncertainty and doubt). Is my country safe? What will happen to my county’s politics, social structure, economics, etc. when the symbol of stability is no longer ‘a fact of life’?

Many ‘British’ espousing people are reticent about these types of questions. The old stereotype of the ‘stiff upper lip’ is alive and well in many of these people. Outpourings of public emotions are ‘not the done-thing, old chap’.

But the majority of the ‘modern’ British espousers have rejected this behaviour in favour something experienced in the lines – generations, genders, ethnicities, politics, geographies, all put aside to share their experiences and emotions in the knowledge that they were bound together in having lived in the most British of circumstances – having a Queen.

These are the stories that define the nation they want to protect. A singular identity to be proud of in a world of ever-changing boundaries of meaning.

Much has been invested and there is still so much to play for. Being grateful for the blessing of being British and a strong desire to keep their culture intact is driven by an emotionally powered desire for the continuance of stability in a ‘better Britain’, which by definition is a different Britain. It can be little wonder that some anxiety and even fear co-exists with the aspirations of these people. Wanting the same but different can seem paradoxical, but this is the world of those who feel British to their core.

Feeling that they are being pulled this way and that – wanting something, but also something that seems at odds with it, at the same time – can stimulate radical creativity in those who can move through the paradox and create something new. This is the stuff of revolutions in all phases of life and the cultures in which it occurs. Stability is sacrificed for creativity.

This has both upsides and downsides for everyone, not just the people being portrayed here.

Just as some welcome the new thinking and behaving, breaking some of the boundaries that stifled their thoughts and behaviours, to others this is disconcerting at the least, and something to be feared and fought against at the more extreme end of their emotions. Moves away from stability and towards radical changes can be felt emotionally as attacks on the roots of their being; a sense their self-identities are no longer safe and secure

One of the factors that emerges in this state of mind is the next Attribute - an outlier for the general population, but ranks sixth, out of 118, among SIBs. This is the AFRAID Attribute:

I believe there is too much violence and lawlessness in society. I'm afraid to walk alone at night in my neighbourhood.

One of the key insights that arise from values research is that ‘big issues’ are often predicated on ‘the little things’. Big issues like ‘law and order’ can frame ideas that lead to changes of governments and subsequent laws. But the big issues are often really no more than small issues amplified in the mind by many people.

Those changes are not usually led by ideological orientations of authorities out of step with the electorate – the changes ‘usually’ reflect what the values-sets of the electorate are looking for.

Feeling safe to walk alone in their own neighbourhood at night is one of the ‘little things’ that power big issues. Feeling unsafe in your ‘safe place’ can and does lead to many people feeling a general sense of disquiet about violence and lawlessness in their country.

This is the most common way that most people understand the world around them. It’s something we all do to some extent. We use our personal feelings, experienced in our local streets and public places (what we know) to project onto the broader social canvas of society (what we don’t know). These experiences and feelings are termed ‘biases’; and understanding them is the basis for understanding both ourselves and others.

This is succinctly summed up in the sentiment expressed in a song by the great Australian singer songwriter, the antipodean Dylan, Paul Kelly, titled “From little things, big things grow”.

To the British espousers of AFRAID this little thing is something big and it makes them angry.

These feelings are part of how they experience today’s Britain (which we’ve established is something they want to maintain) but it is also a part of something they want to make better; to reduce the everyday fears and create a ‘greater place’ - a truly ‘great’ Britain.

This fear can push other natural inclinations these SIBs have concocted to create a greater Britain. But it is not a given that it will be a better place to live – especially if they are unaware of their own biases.

The final over-indexed Attribute presents a dark side to the complex and essentially benign values set of those who assert that being British is an important part of their self-identity. This is an Attribute that is tightly correlated with fear in the human psyche - a sense of anger. It’s a measure of an anger-driven orientation that manifests itself in SIBs as ‘common sense’.

The Attribute is WHIP:

I believe that sex crimes, such as rape and attacks on children, deserve more than mere imprisonment. I think that such criminals ought to be publicly whipped, or worse.

Anger-driven thinking and behaviour often leads to violence. In the short term it seems to solve many problems. But if it doesn’t resolve the reasons for the anger, it often leads to even more violence in the future, rather than the wished-for peace.

People that think this way are not revolutionaries. They do not want radical change; their patience precludes that option. But if change is steady, step-by- step, and those responsible for implementation of the changes are trusted enough, they will live with evolutionary changes. Get the little things right and the big issues take care of themselves. This may be true, but not always. A deeper look may help us understand why.

The WHIP Attribute is one that can be seen as either a means to an end (short sharp shocks), or an end in itself (the way we increase and maintain safety in our society).

Without an awareness of inherent biases, little things like individual sanctions and specific custodial punishments can turn into big things about the nature and foundations of a hoped-for society and the nature of the authorities to maintain it.

Custodial sentences, based and imposed by a centuries-old judicial system, have evolved to preclude public shaming punishments like flogging, or stocks in the village common, let alone public hangings. Yet, crimes against public officials and children are an anathema to the values of today’s Britain. WHIP espousers in general feel there ought to be a ‘different way’ to punish those types of crimes. Perhaps a return to Great Britain as a way of creating a better Britain?

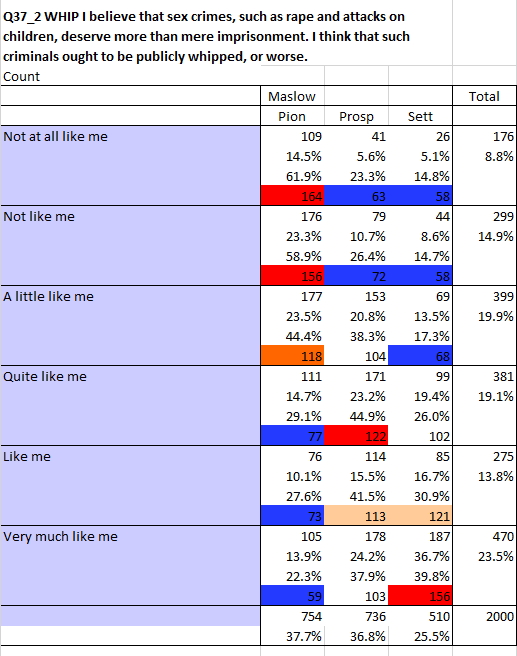

Other British Values Survey data show quite clearly this is not fringe thinking. It is held by a significant portion of the population in varying degrees. Take a look at the table below to see how the different Maslow Groups respond to WHIP:

SIBs are 14% more likely than the population as a whole to agree that WHIP describes them in terms of Very Much Like Me or Like Me. To them WHIP is not just common sense but they agree it is common sense 14% more than the rest of the British population.

On the surface, it would seem that a return to public shaming punishments would satisfy most of the UK populace – and even more so for those identifying as British. A short-term vision of a greater Britain? Or a long-term incremental vision for a greater Britain – a patient step-by-step evolution as authorities are elected to implement and maintain these solutions?

Would these popular measures be seen as ‘short sharp shocks’, possibly with unanticipated consequences, or are they steps toward a society that looks like something from the past?

This is where the concept of a Values War comes to the fore in the vacuum left by the change to a new and unproved government and the death of the 70-year monarch – the “liminal moment” when the light and hope of a future world of possibilities meets the wish for a return of a past world seemingly full of certainties. This is the time when they meet and clash; where little things can become big things.

Normally our analysis would end at this point. The Top 7 Attribute Analysis as used by our many clients to inform, create and drive policies, projects, campaigns and communications to target markets like those who know that being British is an important part of their self-identity.

However, to understand this important group of people, it is useful to take a look at three other Attributes to give a more rounded view.

These three differ from the most espoused Attributes. They are among the least espoused Attributes, i.e. significantly less likely to be espoused than the rest of the British population. One or more may surprise some people but when added to the over-indexed Attributes it will make sense.

Three Significantly Under-Indexed Attributes.

The most under indexed Attribute among our ‘British’ target group is called SELF CRITICAL (118 out of 118).

(Note: The statements used in this section have been modified slightly to reflect them in a positive orientation.)

It is not hard for me to accept myself once I've messed up. I don't criticize myself for negative things I've felt, thought or done.

SIBs are not self -critical. Once something has happened that could be characterized as a mistake or even a crime, they tend to just ‘move on’. This is a phrase that is often used by politicians and others who want critics to stop analysing past mistakes. SIBs are more likely to acknowledge mistakes they make, not spend anytime thinking about them, and happy to ‘move on’. They give short shrift to critics who bemoan their seeming disregard for their actions.

Their critics are themselves often self-critical and feel they can learn from their own mistakes and actions that had negative outcomes. They feel that they learn from these mistakes and become better people afterwards. They believe in rehabilitation; learning from mistakes. Without this rehabilitation of themselves, or others, they believe there can be no hope of resolving issues that lead to bad decisions and bad outcomes. This is an example of a deeply held belief and is perceived as a sign of being able to grow; to wake up to a new way of perception and action.

To the SIBs, this is nonsense. This is the root of ‘Wokeness’. Picking over the remains of the past looking for information that can help understand today’s issues is a complete waste of time to them. “It happened, get over it” is another way of looking at their reaction to new information on any received wisdom about who or what they are. Perhaps the last Prime Minister was like this?

As a result, SIBs are more likely to continue with thoughts and behaviours that they had before they made a mistake. This can mean they stubbornly hold the same views year after year – though never succeeding in pursuit of the ends they desire. In politics this might result in a leader who believes their time has come because of this lack of insight into their failings – but will ultimately fail for the same reason. Basing behaviours on ideologies is a way of not confronting and learning from mistakes. Once again the term 'common sense' is cited as the reason for not being self-critical. The new Prime Minister might be like this?

Research into the SELF-CRITICAL Attribute in other projects reveals that about 70% of the British population IS self -critical and welcomes opportunities to learn from their mistakes – leaving 30% who do not believe this is a useful way to run their lives.

This may explain the failure of programs of rehabilitation that set out with noble purposes – to create better people and a better society – but fail to change targeted behaviours that will achieve this end. Rehabilitation seems to make sense to Self-Critical people. But many people who are not self critical will be resistant to opportunities and situations where they can learn from their mistakes.

Recidivists in jails and prisons are likely to contain many people with this approach to life; on the surface expressing public remorse for past behaviours, yet being paroled/released and returning to the same thoughts and behaviours that lands them back in trouble again.

More dangerously it is also a values set that causes leaders in their companies and countries to practice their power in a manner that harms others. These harms are characterized as mistakes instead of crimes – but they are both driven by a lack of being self-critical and learning from past mistakes.

For SIBs, there is almost a sense of admiration for those who battle against the orthodoxy and plow their own path. They have dreams of doing the same – only held back by their other over-indexed Attributes. But if the situation presents itself – when the bounds of socially defined good behaviour are weakened – they are more likely than the rest of the population to reject orthodoxy in favour of some ‘mindless’ (as opposed to ‘mindful’) behaviour – and feel they don’t have to apologise for it. Typical replies to critics would be along the lines of “get over it, it happened” or “let it go, time to move on”

Pundits and social critics have many times cited examples of people who are swayed by political and populist messages rooted in fear and something expressed through calls for increased punishments. This is something found in the analysis of SIBs. Other commentators have linked this ‘fear and retribution’ orientation to a sense of loss; a sense that their dreams have failed and that they have been ‘left behind’ by life. Some commentators might feel they can make a connection with Britishness as a bulwark against these feelings of being left behind; a protest against the loss of control, uniqueness and identity in a world that is changing in spite of their howls against it.

Well sir, they are completely wrong!

The next Attribute we're looking at is PESSIMISSIM, ranked 114 out of 118. (Remember that the Attribute wording has been ‘reflected’ to express ‘rejection’ as ‘positive’).

I don’t believe I have had a raw deal from life. I have much to expect from the future.

This feeling, that life is OK and fully expected to continue that way, is one of stronger sentiments expressed by SIBs. We have previously seen that they do indeed have fears about safety in their streets and within the country as a whole. This is often linked with people who are not seeing their dreams come true, or have feeling that their situation is fragile and their hopes are liable to dashed in the coming years.

Fear may be felt by those SIBs - but it is unlikely to affect them in a manner portrayed by doomsters and naysayers predicting the downfall of ‘everything we know’.

Paradoxically – holding two different contradictory ideas at the same time – the SIBs agree that they feel the fear, but this is counterbalanced with a quick look at their life. They realize that it has been pretty good so far and see no reason at all that it will change for the worse. They don’t feel left behind at all. They feel pretty good about themselves.

Being pessimistic about life seems to be about other people – not people like themselves.

These SIBs are confident people – who do feel fear for their streets and their country; who can be strict disciplinarians of their children and support harsh punishments for some types of criminal activities; yet are NOT driven by a sense of loss or a pessimism about the future that lazy journalists and commentators might ascribe to them.

It is much more likely that they will react to the doomsayers and ‘explainers’ that they need to - “get over yourself”, “get out more”, or dare it be said, “move on”.

In many ways this typifies a popularized version of being British; the Bulldog spirit. To know what happens, and sometimes it is really scary; that it is just another day of unexpected challenges that will be overcome because “we are British”, i.e. everything usually works out OK, and is never as bad as we were told it would be.

It can be reasonably argued that this is one of drivers that resulted in the UK voting to leave the EU in 2016. Comfortable middle and upper middle-class people, identifying as British, that felt a sense of strength, not hopelessness, when they voted to ‘take back control’ – not out of a sense of being denied, denigrated or left behind by the EU, but out of sense of pride founded on their beliefs that they could build a better Britain.

Populist politicians can and did target their sentiments. These politicians are now largely paying the price, and will continue to pay the price, for the deceitful way they framed the EU Referendum vote. In the latest polls for NatCen Social Research in mid to late August 2022 the electorate had changed its mind about Brexit and would vote differently than in 2016. In 2016 the final count was 52-48 to leave the EU. But if the same vote was taken today (mid-September 2022), the result would be 55-45 to remain. It can be conjectured that many of those who have changed their minds would be among the group who are proud to be British and are not seeing or feeling that the promises made in 2016 are being delivered.

If this is true - and there are good reasons to believe it is true - it is also true that they would be unlikely to want to have another referendum, even if they would likely vote differently. That is not the way they think.

SIBs are comfortable with evolutionary changes – small steady steps – rather than massive, unsettling changes. In their minds, Brexit represented a return to a less complex and comforting, pink tinged past – a small evolutionary change. Withdrawing from a larger, more complex, more diverse society and settling back into a smaller, more homogenous society seems an obvious choice - ‘just a small step back‘ - in the expression of their pride of being British. Polling in the immediate wake of the referendum showed the consternation of some voters that the process would be subject to negotiations for years – the vote was about something big, not a small incremental step back.

The very act of voting was also in keeping with their values – physically acting and moving on. They are not likely just to sit back and moan about issues and behaviours. They change their minds if they think they got something wrong - with no compunction about the change of mind.

This basic form of pragmatism, dealing with the world as it exists, with many issues and circumstances beyond their control, is made simpler if they just accept it and remain positive in themselves.

We measure this in the STUCK Attribute (ranked 112 out of 118). SIBs do NOT feel stuck (again be aware of the rewording make the statement positive):

When things go wrong for reasons that I can't control, I don’t get stuck in negative thoughts about them. It's really easy for me to accept such situations.

This is a positive pragmatism that leads SIBs easily to shift their positions on any issue – whether it is about what the past meant to them or what they used to believe that the future should be. They have an aversion to wallowing in negative thought.

Remembering some of the Attributes that measure fear and retribution, this final Attribute helps understand the basis of their positive pragmatism. The world may be full of danger, both personally and socially; the harsh punishments they want for certain criminal may not be occurring; but instead of moaning about it, they tend to accommodate it in a positive fatalism. They take personal responsibility for their own thoughts and behaviours and make choices that allay feelings of inadequacy.

Psychologically, this is a healthy reaction to circumstances beyond their control and is an amplification of their trust in authorities, and their basic patience. Having patience doesn’t translate into a depressed acceptance (pessimism) for these SIBs. Their acceptance acknowledges a situation they wouldn’t have chosen – but, through changing their attitudes about the situation, they can maintain their identity of being British even as the meaning of being British changes – and they remain positive as the meaning changes.

Their ‘moving on’ dynamic enables them to remain positive no matter what the circumstances. Many of cultural stories that attract them – representations of what it means to be British – demonstrate the homogenous and changeable nature of being British that arises from this belief system.

Tales of a class-stratified culture where social lines were acknowledged and observed in everyday language, e.g. “upper class/middle class/working class”, “upstairs-downstairs”, “knowing your place” that had defined self-perceptions for centuries, were suddenly, not gradually, changed by WW2. All Londoners were suddenly, repeatedly, at random intervals pushed together in the deep Tubes in very bad circumstances. The narratives portray this as a time when everyone came together in their strengthened sense of Britishness (or Englishness) – a meta identity that was a positive pragmatic change of mind that replaced the long-term identities that had previously defined the population. The opening of homes and facilities of large landholders and merchant estates to local populations in the ‘war effort’ in other parts of the country helped the new narrative and identity gain cultural traction.

Britain under attack – a situation outside its control – led to a narrative of positive pragmatism. A refusal to fall into negativity and passivity that can come from the pessimism.

Pessimism as NOT being at the core of Britishness is still valorised among these people. The narrative that a ‘nation of shop keepers’ in times of dire distress came together with the ‘Dunkirk spirit’ to save British troops is real, and a new Britishness emerged. It was at once both a demonstration and a tale of togetherness in adversity, of those who took control and created a different version of being British. This new narrative of Britishness turned quite quickly to identifying themselves as having the “Bulldog spirit”. Not everyone identified with this change, but those who strongly identified as being British would have been more likely to adopt the description with pride.

Over the last decade some current members of the newly formed government of Liz Truss, and many members of the recent past government, have tapped into the same spirit and succeeded in portraying the country at war with foreigners – with the EU, with the European Court of Human Rights, with immigrants, etc. – and have cynically triggered many of the positive orientations of the self-identified British. In a way that is consistent with their values. Many SIBs easily bought into the narrative and proudly voted to 'take back control'. But just as easily many of them have changed their minds as they experience circumstances they had not anticipated with their original Brexit vote.

If the Bulldog spirit – a refusal to abandon their country to non-British ideologies – can be deployed in efforts to bring the country together in a true war against forces ‘outside personal control’ (like the many different manifestations of climate change, NOT a war with Russia!) it is possible that this could be attractive to these positive pragmatists.

This is something that all environmental and humanitarian NGOs and charities have failed to understand and develop for decades. But using this insight is way of changing the dynamic.

|

Summary: The death of a female Monarch who had occupied the throne for 70 years, led to the mass public mourning and private grief of millions of people who had never met or personally knew the Queen. The time of mourning presented a time of reflection. Many people asked a question that was rarely raised during her reign. At the same time a new and untested head of the Conservative Party took over as Prime Minster. Which also stimulated a similar question. Both questions – about the essential nature of being British – were posed in a volatile political and social context of multiple systemic stability-threatening processes not immediately amenable to easy solutions. This time has been characterized as a liminal moment – the time between what was, and what will happen. A time when the old rules and biases that worked, no longer work as well or even don’t work at all; and the future is not coherently perceived or organized yet - just a lot of uncertain, complex and ambiguous options. We have used data and insights generated by the British Values Survey which posed questions that explored the values system of people who know that an important part of their identity was ‘being British’. This has aided the understanding of what the values, beliefs and motivations of these self-aware people were, before two historical occurrences came together in the contextual confluence of deep systemic issues. We have examined the SIBs’ internal psychological dynamic, as well as their reactions to external events and circumstances. The data and emergent story provided – of fear, anxiety, a need for certainty, a natural deference to authority, that leads to a wish for harsh retributions; but also a desire for a romantized version of reality that could be achieved through the deployment of motivations of other aspects of their values system; a powerful inclination not to dwell on negative thoughts and behaviours, to ‘move on’ in the overwhelming belief that they are capable of dealing with any situation that confronts them. This is a version of Britishness that has its roots deep in the history, narratives, myths and stories told and retold in schools, libraries, widely different forms of media and among themselves in their families over dinner tables and over pints and glasses of wine in the pubs and clubs the length and breadth of the country. Through examining the values system of those most self-identified as British it is possible to get a feeling of where they were before the liminal moment; understand how they are reacting in the moment; and, most importantly, how are they likely to interact with the rest of the population as the country enters a series of simultaneous ‘new eras’. |